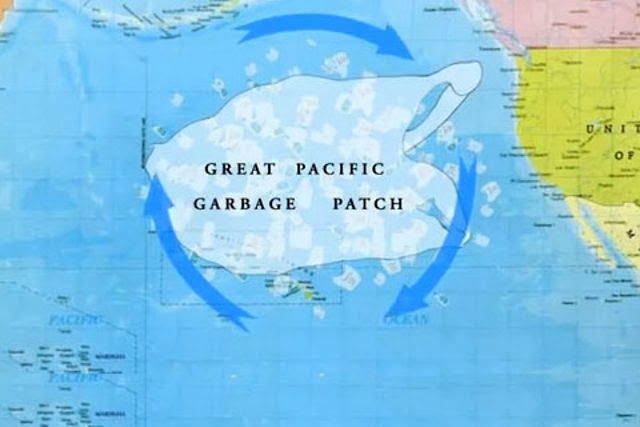

They specifically indicated the North Pacific Gyre. Extrapolating from findings in the Sea of Japan, the researchers hypothesized that similar conditions would occur in other parts of the Pacific where prevailing currents were favorable to the creation of relatively stable waters. Researchers found relatively high concentrations of marine debris accumulating in regions governed by ocean currents. The description was based on research by several Alaska-based researchers in 1988 who measured neustonic plastic in the North Pacific Ocean.

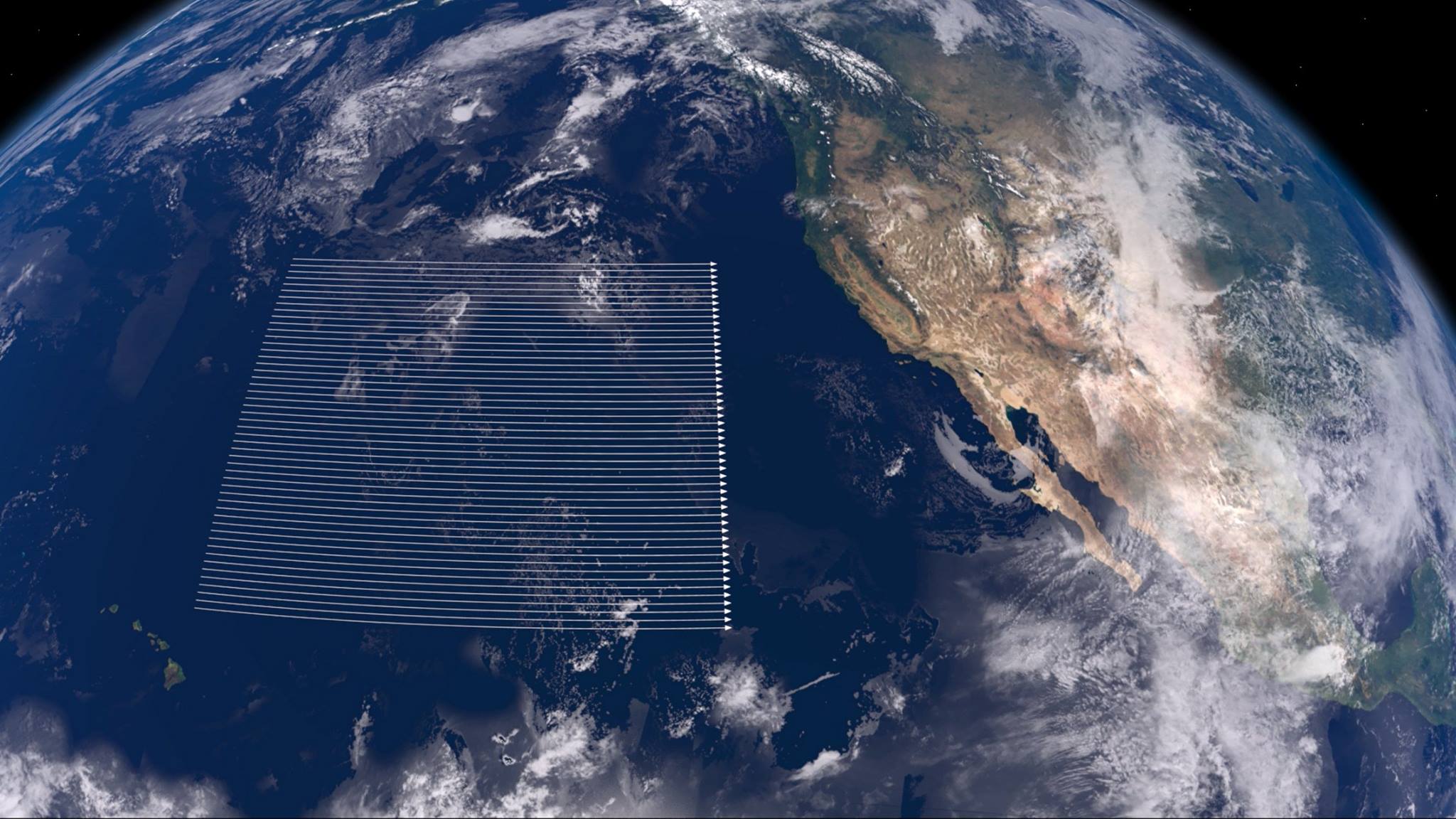

GREAT PACIFIC GARBAGE PATCH FROM SPACE PATCH

The patch was described in a 1988 paper published by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The area of increased plastic particles is located within the North Pacific Gyre, one of the five major ocean gyres. This growing patch contributes to other environmental damage to marine ecosystems and species. A similar patch of floating plastic debris is found in the Atlantic Ocean, called the North Atlantic garbage patch. The gyre contains approximately six pounds of plastic for every pound of plankton. Estimated to be double the size of Texas, the area contains more than 3 million short tons (2.7 million metric tons) of plastic. The patch is believed to have increased "10-fold each decade" since 1945. Research indicates that the patch is rapidly accumulating. Some of the plastic in the patch is over 50 years old, and includes items (and fragments of items) such as "plastic lighters, toothbrushes, water bottles, pens, baby bottles, cell phones, plastic bags, and nurdles." The small fibers of wood pulp found throughout the patch are "believed to originate from the thousands of tons of toilet paper flushed into the oceans daily." Researchers from The Ocean Cleanup project claimed that the patch covers 1.6 million square kilometres (620 thousand square miles) consisting of 45–129 thousand metric tons (50–142 thousand short tons) of plastic as of 2018. This is because the patch is a widely dispersed area consisting primarily of suspended "fingernail-sized or smaller"-often microscopic-particles in the upper water column known as microplastics. The gyre is divided into two areas, the "Eastern Garbage Patch" from California to Hawaii, and the "Western Garbage Patch" extending from Hawaii to Japan.ĭespite the common public perception of the patch existing as giant islands of floating garbage, its low density (4 particles per cubic metre (3.1/cu yd)) prevents detection by satellite imagery, or even by casual boaters or divers in the area. The collection of plastic and floating trash originates from the Pacific Rim, including countries in Asia, North America, and South America. It is located roughly from 135°W to 155°W and 35°N to 42°N. The Great Pacific garbage patch (also Pacific trash vortex and North Pacific Garbage Patch ) is a garbage patch, a gyre of marine debris particles, in the central North Pacific Ocean. By clarifying their mode of existence, we are learning to come to terms more generally with the furniture of the technoscientific world – where, for example, the 'dead matter' of classical physics is becoming the 'smart material' of emerging and converging technologies.The patch is created in the gyre of the North Pacific Subtropical Convergence Zone.

With their promise of sustainable innovation and a technologically transformed future, these objects are highly charged with values and design expectations. Together they offer fascinating stories and novel analytic concepts, all the while opening up a space for reflecting on the specific character of technoscientific objects. Seventeen scholars from history and philosophy of science, epistemology, social anthropology, cultural studies and ethics each explore a research object in its technological setting, ranging from carbon to cardboard, from arctic ice cores to nuclear waste, from wetlands to GMO seeds, from fuel cells to the great Pacific garbage patch.

The objects of technoscience tell a different story that concerns the power, promise and potential of things – not what they are but what they can be. What kind of stuff is the world made of? What is the nature or substance of things? These are ontological questions, and they are usually answered with respect to the objects of science.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)